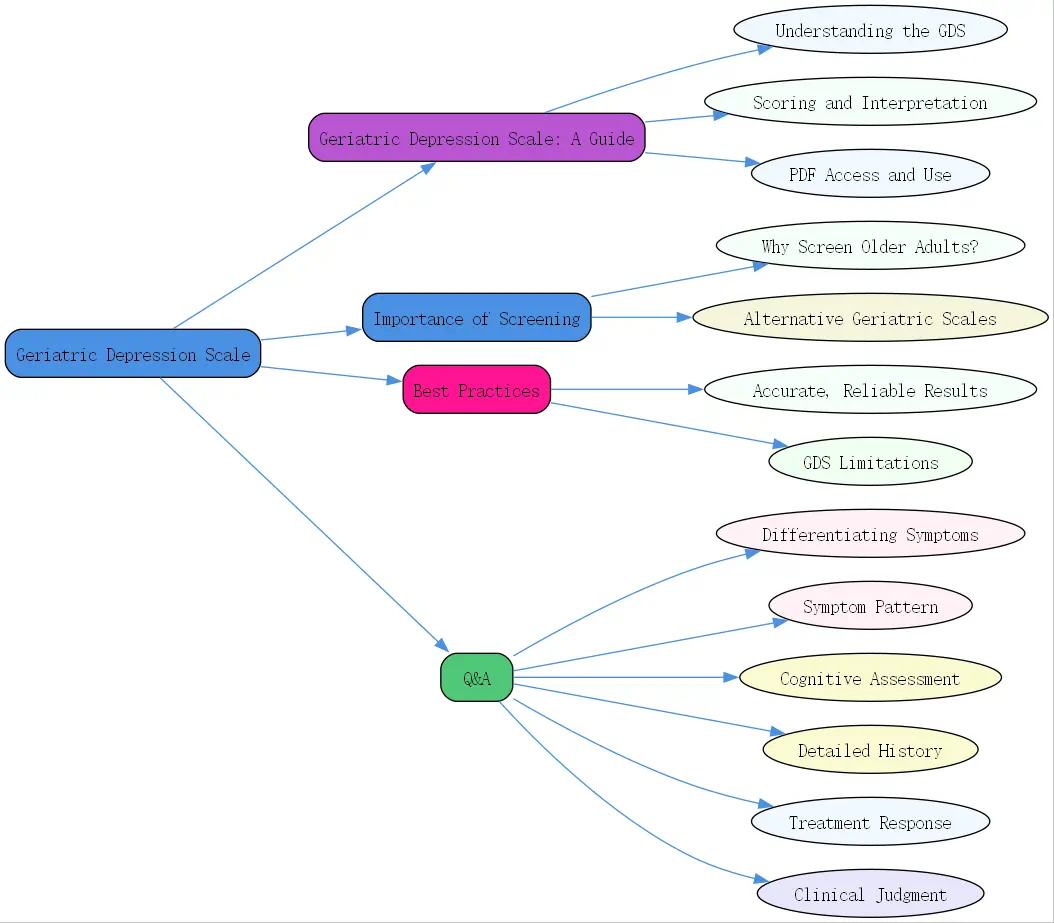

Geriatric Depression Scale: A Comprehensive Guide

Depression in older adults is a significant concern, often overlooked or mistaken for other age-related changes. Effectively identifying seniors who may be struggling is crucial for their well-being. Thankfully, tools exist to aid in this process. Like many mental health assessments sought by clinicians today, the ideal instrument is quick, validated, easy to use, and economical. One cornerstone tool in geriatric care is the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), designed specifically for older populations. This guide explores the GDS, its scoring, accessibility, and importance in promoting mental health for seniors.

Understanding the Geriatric Depression Scale

Navigating the complexities of mental health in later life requires specialized tools. The GDS stands out as a widely recognized and utilized instrument. Understanding its background and purpose is the first step toward effective application.

- What is the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)?

The Geriatric Depression Scale, often abbreviated as GDS, is a self-report questionnaire specifically developed to screen for symptoms of depression in older adults. Created by Yesavage and colleagues in the early 1980s, it was designed to be simple to administer and score, avoiding questions related to somatic symptoms that could overlap with physical illnesses common in aging. Its focus is primarily on the affective aspects of depression, making it particularly useful for the geriatric population. Several versions exist, including the original 30-item scale (GDS-30) and more commonly used shorter versions like the 15-item (GDS-15) and even 5-item (GDS-5) forms, offering flexibility depending on the clinical setting and patient capacity.

The Geriatric Depression Scale, often abbreviated as GDS, is a self-report questionnaire specifically developed to screen for symptoms of depression in older adults. Created by Yesavage and colleagues in the early 1980s, it was designed to be simple to administer and score, avoiding questions related to somatic symptoms that could overlap with physical illnesses common in aging. Its focus is primarily on the affective aspects of depression, making it particularly useful for the geriatric population. Several versions exist, including the original 30-item scale (GDS-30) and more commonly used shorter versions like the 15-item (GDS-15) and even 5-item (GDS-5) forms, offering flexibility depending on the clinical setting and patient capacity.

- Purpose and Applications of the GDS

The primary purpose of any geriatric scale for depression, including the GDS, is screening – identifying individuals who may have depression and warrant further, more comprehensive evaluation. It’s not intended as a standalone diagnostic tool, a crucial point echoed in general mental health assessment principles. The GDS is valuable in various settings, including primary care clinics, hospitals, nursing homes, and community health programs. Its ease of use makes it practical for busy clinicians needing a quick baseline assessment, aligning with the modern need for efficient, validated screening instruments. It helps flag potential issues early, facilitating timely intervention.

- Benefits of Using the GDS in Geriatric Mental Health

The GDS offers several advantages. Its simple yes/no format is generally well-tolerated by older adults, including those with mild to moderate cognitive impairment who might struggle with more complex Likert scales. Administration is quick, typically taking 5-10 minutes for the GDS-15. Furthermore, the scale has been extensively researched and validated across diverse populations and settings, establishing its reliability as a screening tool. Its focus on mood rather than physical symptoms reduces the likelihood of false positives due to comorbid physical conditions. As a freely available tool, it also meets the need for economical assessment options in resource-constrained environments.

Geriatric Depression Scale Scoring and Interpretation

Once the GDS is administered, understanding how to score it and interpret the results is essential. The process is straightforward, but careful interpretation within the clinical context is key. Remember, screening scores indicate risk, not a definitive diagnosis.

- Step-by-Step Guide to Geriatric Depression Scale Scoring

Geriatric depression scale scoring is typically based on the number of “”depressed”” answers circled. For the commonly used GDS-15, specific answers indicate potential depressive symptoms. For example, answering “”no”” to “”Are you basically satisfied with your life?”” or “”yes”” to “”Do you often feel helpless?”” would typically count as one point. Each version (GDS-30, GDS-15, GDS-5) has its specific scoring key, usually provided with the scale itself. Tally the number of responses that align with the keyed “”depressed”” answers to arrive at the total score.

- Interpreting GDS Scores: What Do the Numbers Mean?

The total score provides an indication of the likelihood and potential severity of depression. A higher score suggests a greater number of endorsed depressive symptoms. It’s vital to remember that this score reflects the patient’s self-report at a specific point in time. Context matters – consider recent life events, physical health status, and cognitive function when evaluating the score. The numbers provide a valuable data point, but clinical judgment remains paramount.

- Cut-off Scores and Severity Levels of Depression

Standardized cut-off scores help categorize the results. For the GDS-15, commonly used thresholds are:

0-4: Normal / Not Depressed 5-8: Suggestive of Mild Depression 9-11: Suggestive of Moderate Depression 12-15: Suggestive of Severe Depression It’s crucial to use these cut-offs as guidelines. A score below 5 doesn’t definitively rule out depression, and a score above 5 requires further clinical assessment to confirm a diagnosis and determine the appropriate course of action. These scales help identify individuals needing a closer look, aligning with the principle of using broad screening before narrowing focus.

Accessing and Utilizing the Geriatric Depression Scale PDF

Accessibility is a key feature of the GDS, making it a practical choice for many practitioners. Knowing where to find reliable versions and how to integrate them is important.

- Where to Find the Geriatric Depression Scale PDF

The GDS is widely available, often free for clinical and research use. Reputable sources for a geriatric depression scale pdf include university websites associated with geriatric medicine or psychiatry departments (e.g., Stanford University, which hosts resources related to the scale’s development `[External Link to Stanford GDS Page – Placeholder]`), geriatric mental health foundations, and some government health agency sites. Ensure you are obtaining the scale from a credible source to guarantee you have the correct version and scoring instructions. Always respect any copyright or usage terms associated with the specific version you download.

The GDS is widely available, often free for clinical and research use. Reputable sources for a geriatric depression scale pdf include university websites associated with geriatric medicine or psychiatry departments (e.g., Stanford University, which hosts resources related to the scale’s development `[External Link to Stanford GDS Page – Placeholder]`), geriatric mental health foundations, and some government health agency sites. Ensure you are obtaining the scale from a credible source to guarantee you have the correct version and scoring instructions. Always respect any copyright or usage terms associated with the specific version you download.

- Considerations for Using the PDF Version

Using a PDF version allows for easy printing and administration. Ensure the printout is clear and legible, with adequate font size for older adults who may have visual impairments. Consider the environment – administration should occur in a private, comfortable setting. While digital options for some assessments exist, printable PDFs remain a practical, low-cost staple, especially when paid digital platforms aren’t feasible.

- Integrating the GDS into Clinical Practice

The GDS can be seamlessly integrated into routine geriatric assessments or initial mental health evaluations. Its brevity allows it to be completed during a standard appointment or while the patient is waiting. Documenting the score provides a valuable baseline. It can be used periodically to monitor symptoms or treatment response, fulfilling the evaluation aspect mentioned in assessment tool frameworks. Consistent use helps normalize mental health screening as part of comprehensive elder care. Consider exploring further resources on senior wellness at BrainTalking `[Link to related BrainTalking article on elderly mental health – Placeholder]`.

The Importance of Geriatric Depression Screening

Screening for depression isn’t just a procedural step; it’s a critical component of holistic care for older adults. Understanding the prevalence and impact underscores its necessity.

Why Screen for Depression in Older Adults?

Depression significantly impacts the health and quality of life of seniors, yet it often goes undetected and untreated. Proactive screening is essential to change this narrative.

- Prevalence of Depression in Geriatric Populations

While not a normal part of aging, depression is common among older adults. Estimates vary, but significant depressive symptoms affect a substantial percentage of seniors, particularly those in healthcare settings or with chronic illnesses. Late-life depression is often underdiagnosed because symptoms can mimic other conditions or be attributed solely to aging. This hidden prevalence highlights the urgent need for effective screening tools like the GDS.

- Impact of Untreated Depression on Older Adults’ Well-being

Untreated depression in seniors has serious consequences. It can exacerbate physical health problems, increase disability, impair cognitive function, reduce quality of life, and elevate the risk of mortality, including suicide. Depression can hinder recovery from illness or surgery and lead to social isolation. Addressing depression is not just about improving mood; it’s about enhancing overall health, function, and longevity.

- Early Detection and Intervention Strategies

Screening facilitates early detection, which is paramount for effective intervention. Identifying depression early allows for prompt implementation of treatment strategies, which may include psychotherapy, medication, lifestyle changes, or a combination thereof. Early intervention significantly improves outcomes, reduces suffering, and can prevent the progression to more severe or chronic depression. Tools like the GDS are the first step in this crucial pathway.

Alternative Geriatric Scales for Depression

While the GDS is a cornerstone, it’s not the only tool available. Depending on the specific clinical context or patient population, other scales might be considered.

- Comparing the GDS with Other Assessment Tools

Other commonly used scales include the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), mentioned in broader mental health assessment discussions, which screens for depression severity based on DSM criteria but includes somatic items the GDS avoids. The Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) is designed for individuals with significant cognitive impairment where self-report is difficult, relying instead on observation and caregiver input. Each geriatric scale for depression has strengths and weaknesses; the choice depends on the assessment goals and patient characteristics.

- Brief Depression Screeners for Older Adults

Beyond the GDS-15, even shorter screeners exist, like the GDS-5 or the PHQ-2 (a two-item version of the PHQ-9). These ultra-brief tools can be useful for very rapid screening in busy settings like primary care or emergency departments to quickly identify individuals needing a more detailed assessment. Their brevity makes them highly feasible but generally less sensitive than longer forms.

- Selecting the Right Scale for Specific Needs

The choice of scale should be guided by several factors: the patient’s cognitive status, the presence of physical comorbidities, the time available for assessment, the setting (clinical vs. research), and the specific information needed (screening vs. severity monitoring). As highlighted in general assessment principles, understanding the population being served and the tool’s validation within that group is crucial. Sometimes, using more than one tool or approach provides a more comprehensive picture.

Best Practices for Administering the Geriatric Depression Scale

How the GDS is administered can influence the accuracy and reliability of the results. Following best practices ensures a more effective screening process.

Ensuring Accurate and Reliable Results

Creating the right conditions and approach for administration helps maximize the value of the GDS screening. Thoughtful interaction builds trust and encourages honest responses.

- Creating a Comfortable and Supportive Environment

Administer the scale in a private, quiet setting where the older adult feels comfortable and unhurried. Ensure confidentiality. Approach the task with sensitivity and empathy, explaining the purpose of the questionnaire clearly – that it helps understand their feelings and well-being. A supportive atmosphere can reduce anxiety and encourage more open self-reporting.

- Providing Clear and Concise Instructions

Explain how to respond to the questions (usually simple yes/no). Read the questions aloud clearly if the patient has visual impairments or difficulty reading, or allow them to read and complete it themselves if preferred and able. Ensure they understand they should reflect on their feelings over the past week or two. Avoid interpreting questions for them; simply clarify instructions if needed.

- Addressing Cultural and Linguistic Considerations

As with any assessment tool, cultural background and language can influence responses. Be mindful of potential cultural variations in expressing emotional distress. If language barriers exist, use a validated translation of the GDS if available, administered by a qualified interpreter or bilingual staff member whenever possible. Being aware of cultural nuances aligns with best practices in all mental health assessments, ensuring the tool is appropriate for the individual.

Limitations of the Geriatric Depression Scale

While valuable, the GDS is not without limitations. Understanding these helps clinicians use the tool appropriately and supplement it when necessary.

- Factors That May Influence GDS Scores

Severe cognitive impairment can make self-report unreliable, limiting the GDS’s utility in individuals with advanced dementia. Significant sensory impairments (vision, hearing) can pose challenges to administration if not adequately accommodated. Furthermore, some older adults may be reluctant to endorse depressive symptoms due to stigma or other personal factors, potentially leading to underreporting. Physical illness symptoms, while minimized compared to other scales, can sometimes still overlap slightly.

- The Importance of Clinical Judgment

Crucially, the GDS score should never replace clinical judgment. As emphasized in broader assessment contexts, rating scales do not automatically equal a diagnosis. The score is one piece of information within a larger clinical picture that includes history, observation, collateral information (from family or caregivers, when appropriate and with consent), and potentially other assessments. A clinician must synthesize all available data.

- When to Use Additional Assessment Methods

If the GDS score is elevated, or if clinical suspicion remains high despite a low score, further assessment is warranted. This might involve a more detailed clinical interview focusing on diagnostic criteria for depression (e.g., using DSM-5 or ICD criteria), assessing suicide risk, ruling out underlying medical causes, or using different assessment tools, perhaps including those that gather observational data or informant reports, especially if cognitive impairment is a concern. BrainTalking emphasizes a comprehensive approach to mental wellness.

If the GDS score is elevated, or if clinical suspicion remains high despite a low score, further assessment is warranted. This might involve a more detailed clinical interview focusing on diagnostic criteria for depression (e.g., using DSM-5 or ICD criteria), assessing suicide risk, ruling out underlying medical causes, or using different assessment tools, perhaps including those that gather observational data or informant reports, especially if cognitive impairment is a concern. BrainTalking emphasizes a comprehensive approach to mental wellness.

- The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) is a vital screening tool for identifying potential depression in older adults.

- It is valued for its simplicity, speed, focus on mood, and validation in geriatric populations.

- Geriatric depression scale scoring involves summing points for answers indicative of depression, with established cut-offs suggesting severity (e.g., 5+ on GDS-15 warrants attention).

- A readily available geriatric depression scale pdf allows for easy integration into clinical practice, but credible sources should be used.

- Screening is crucial due to the high prevalence and severe impact of untreated depression in seniors.

- While effective, the GDS has limitations (e.g., severe cognitive impairment) and scores must be interpreted with clinical judgment. It is a screening, not a diagnostic tool.

- Best practices include creating a supportive environment and considering cultural factors.

Q&A Section

Q: How can clinicians differentiate symptoms identified by the Geriatric Depression Scale from symptoms of dementia or physical illness?

A: This is a critical challenge in geriatric assessment. While the GDS intentionally minimizes focus on somatic symptoms common in physical illness, overlap can still occur (e.g., fatigue, changes in sleep). Differentiating from dementia is also key. Here’s a multi-faceted approach:

1. Symptom Pattern: Depression symptoms (especially captured by the GDS’s focus on mood, anhedonia, hopelessness) often have a more distinct onset and may fluctuate more than the gradual cognitive decline typical of dementia. Look for core mood symptoms like persistent sadness, loss of interest, feelings of worthlessness – these are less characteristic of dementia itself, though mood changes can co-occur. 2. Cognitive Assessment: Use specific cognitive screeners (like the MoCA or Mini-Cog) alongside the GDS. While depression can cause cognitive complaints (“”pseudodementia””), formal testing often reveals different patterns than primary dementia. Performance on cognitive tests might improve if depression is successfully treated. 3. Detailed History: A thorough history from the patient (and potentially caregivers) about the onset, duration, and nature of symptoms is vital. Was there a decline in mood before significant memory loss? Are physical symptoms (like pain or fatigue) better explained by a documented medical condition? 4. Response to Treatment: Sometimes, a trial of antidepressant treatment (if appropriate) can clarify the picture. Significant improvement in mood and potentially associated cognitive complaints might suggest depression was the primary driver. 5. Clinical Judgment: Ultimately, integrating information from the GDS, cognitive tests, medical history, physical exam, patient interview, and possibly caregiver reports is essential. No single score provides the answer; it requires careful clinical synthesis. Remember, depression and dementia or physical illness often co-exist, requiring treatment for all conditions.