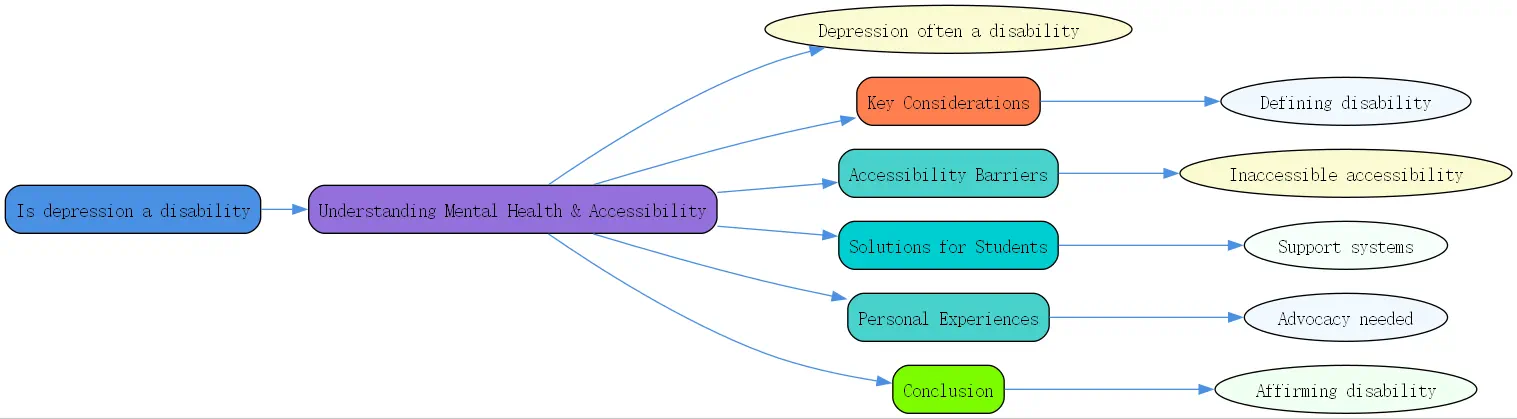

Is Depression a Disability? Understanding Mental Health and Accessibility

Mental health is increasingly part of our public conversation, yet many questions remain. One significant question often asked is: is depression a disability? The short answer is complex, but often, yes. Understanding this is crucial, particularly when navigating systems like higher education or the workplace, where support and accommodations can make a vital difference. As awareness grows, so does the need for clarity on how conditions like depression impact daily life and functional capacity.

This recognition isn’t just about labels; it’s about access. For many, particularly students grappling with the pressures of academia, acknowledging that depression is a disability opens doors to necessary support systems. Unfortunately, as highlighted by experts like Kelly Davis at Mental Health America (MHA), accessing these systems can be surprisingly difficult, creating a paradox of “”inaccessible accessibility.”” Let’s delve into what defines disability, how depression fits, the barriers faced, and the path toward better support.

Navigating the Question: Is Depression Disability? Key Considerations

Understanding whether depression qualifies as a disability requires looking at established definitions. Legally, particularly under frameworks like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the United States, a disability is defined as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. This includes activities like concentrating, thinking, communicating, sleeping, eating, and working or learning. Depression, especially in its more severe forms, can significantly impair these functions.

Medically, diagnoses like Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) involve persistent symptoms such as low mood, loss of interest, fatigue, changes in sleep or appetite, difficulty concentrating, and feelings of worthlessness. When these symptoms reach a severity level that interferes significantly with daily functioning, the condition aligns with the criteria for disability. It’s not the diagnosis alone, but the impact of the condition on the individual’s life that determines disability status. Many individuals find their ability to engage in education, employment, or even basic self-care profoundly affected.

The question “”is depression disability?”” often arises because the condition’s intensity can fluctuate. Some people experience chronic, persistent depression, while others face episodic bouts. However, even episodic depression can be disabling during acute periods. The concept of “”is depression a disability snaps“” touches on this – sudden, severe episodes can abruptly render someone unable to function normally. These moments highlight the need for flexible and responsive support systems that recognize the variable nature of mental health conditions.

Ultimately, affirming that depression is a disability for many isn’t about minimizing the experiences of those with milder symptoms. Instead, it validates the significant struggles of those whose condition substantially limits their lives. This recognition is the first step toward ensuring individuals receive appropriate accommodations and support, enabling them to participate more fully in society, education, and work. It requires a shift from viewing depression solely as a transient mood state to understanding its potential as a serious, limiting health condition. [External Link to ADA National Network]

Accessibility Barriers and Solutions: Supporting Students with Depression

Despite legal recognition, accessing support for depression as a disability, especially in higher education, presents significant hurdles. Student perspectives reveal a landscape fraught with challenges. Many students, like MHA’s Kelly Davis shared from her own experience, are unaware that their mental health condition could qualify them for disability accommodations until they reach a crisis point, often on the verge of dropping out. This lack of awareness is a critical barrier.

The situation is compounded by the ongoing campus mental health crisis. Even before 2020, universities saw a dramatic increase in students seeking mental health support. As Davis noted, decades of advocacy encouraged young people to seek help, yet the infrastructure to provide that help often wasn’t built. This leads to long waiting lists for counseling services – sometimes weeks long – a timeframe that can feel like an eternity for someone in acute distress, potentially spanning a significant portion of a semester.

This strain on resources directly impacts students needing accommodations for depression. Disability service offices may be understaffed or follow rigid documentation processes that are difficult for students navigating mental health challenges to complete. Furthermore, the stigma surrounding mental illness can prevent students from seeking help or disclosing their condition, fearing judgment from peers, faculty, or administrators. The MHA report, based on surveys with college students, underscores these issues, finding that many learn about accommodations too late, potentially after accumulating significant debt without completing their education.

To address these barriers, several strategies are essential. Firstly, universities must proactively educate students that mental health conditions like depression can qualify as disabilities and detail the available accommodations. This information should be integrated into orientations, health services, and academic advising, moving beyond generic “”seek help”” messages. Simplifying the process for requesting accommodations, while maintaining necessary standards, is also crucial. This might involve offering more flexible documentation options or providing navigators to assist students through the process.

Expanding mental health resources, including counseling staff and peer support programs, is vital to meet the increased demand and reduce wait times. Peer support, leveraging lived experience, can be particularly effective in reducing stigma and helping students navigate university systems. Finally, fostering a campus culture that genuinely supports mental well-being requires training for faculty and staff on recognizing distress and responding compassionately, creating an environment where seeking help is normalized and encouraged. [Link to related BrainTalking article on Student Mental Health Resources]

Personal Experiences and Advocacy: Depression is a Disability

The statement “”depression is a disability“” gains powerful resonance through personal stories. Hearing from individuals who have navigated academic or professional life while managing depression illuminates the real-world challenges and the critical importance of accommodations. Kelly Davis’s account of nearly dropping out of college before discovering disability services is a potent example echoed by countless others who felt isolated and overwhelmed by their condition. These narratives move the conversation beyond abstract definitions.

Sharing lived experiences serves multiple purposes. It chips away at the persistent stigma surrounding mental illness, showing that depression is a health condition, not a character flaw. It also provides concrete examples of how depression impacts functioning – difficulty meeting deadlines, challenges with concentration in lectures, struggles with attendance, or social withdrawal affecting group projects. When institutions understand these tangible impacts, the need for accommodations like deadline extensions, note-takers, or reduced course loads becomes clearer.

The journey to securing accommodations itself can be an arduous process, adding another layer of stress for someone already struggling. It often involves obtaining formal diagnoses, gathering extensive medical documentation, and navigating bureaucratic procedures within disability services offices. This process can feel invalidating or overly demanding. Advocacy groups and peer support networks play a crucial role here. Organizations like Mental Health America work to improve policies and systems, while peer supporters offer invaluable guidance, empathy, and practical advice based on their own experiences, reinforcing that asking for help is a sign of strength.

Hearing success stories – students who thrived with accommodations, employees who maintained productivity with workplace adjustments – provides hope and demonstrates the positive outcomes of recognizing is depression disability status when appropriate. These successes underscore that with the right support, individuals with depression can achieve their academic and professional goals. Their journeys highlight the need for systems that are not just technically compliant but truly accessible and supportive. [Link to related BrainTalking article on Workplace Accommodations]

Conclusion: Affirming That Depression is a Disability

Throughout this discussion, we’ve explored the multifaceted question: is depression a disability? The evidence, from legal definitions under the ADA to the lived experiences of individuals navigating significant mental health challenges, points to a clear affirmative for many. Severe depression can substantially limit major life activities, meeting the criteria for disability and necessitating support and accommodations. Recognizing this is fundamental to fostering inclusive environments in education, work, and society at large.

We’ve seen how crucial awareness is – many individuals, particularly students, remain unaware that their condition qualifies them for potentially life-altering support. The accessibility of existing disability services often falls short, hampered by resource limitations, complex procedures, and persistent stigma. Addressing the campus mental health crisis requires not only more counselors but also a systemic approach that includes proactive education about accommodations and streamlined access pathways.

Personal stories and advocacy efforts are vital in driving change. They personalize the issue, challenge stigma, and highlight the tangible benefits of appropriate support systems. Affirming that depression is a disability isn’t just semantics; it’s a call for empathy, understanding, and action. It means creating systems that acknowledge the reality of mental illness and provide the tools individuals need to thrive. At BrainTalking, we believe in empowering individuals with knowledge and support for their mental health journey.

Moving forward requires a collective effort. Institutions need to invest in robust, accessible mental health and disability services. Individuals must feel empowered to seek help without fear of judgment. Policymakers must ensure protective legislation is effectively implemented. By working together, we can ensure that everyone grappling with depression receives the understanding and support they deserve, enabling them to lead fulfilling lives.

- Definition: Depression can qualify as a disability under legal definitions (like the ADA) if it substantially limits one or more major life activities (e.g., concentrating, working, learning).

- Variability: Not all depression is disabling; severity, duration, and impact on functioning are key factors. Even episodic depression can be disabling during acute phases.

- Awareness Gap: Many individuals, especially students, are unaware that mental health conditions like depression can qualify for disability accommodations.

- Accessibility Barriers: Challenges include lack of awareness, stigma, strained campus mental health resources (long waits), and complex accommodation request processes.

- Solutions: Increase proactive education about accommodations, streamline access, expand resources (counseling, peer support), and foster supportive campus/workplace cultures.

- Lived Experience: Personal stories and advocacy are crucial for reducing stigma, demonstrating need, and improving support systems.

Question: What types of accommodations can someone with depression receive in school or at work?

Answer: Accommodations for depression are individualized based on how the condition impacts the person’s specific functioning in that environment (school or work) and the essential requirements of their role or program. The goal is to provide equal opportunity, not lower standards. Common examples include:

- Flexibility: Modified attendance policies, flexible deadlines for assignments or projects, flexible work hours, or the ability to work remotely sometimes.

- Environmental Adjustments: Reduced-distraction workspace or testing environment, preferential seating in classrooms.

- Task Modification: Breaking down large assignments or projects into smaller steps, written instructions instead of verbal ones (to aid concentration/memory), permission to record lectures or meetings.

- Support: Access to note-takers in class, regular check-ins with supervisors or advisors, permission for breaks as needed to manage symptoms.

- Leave: Extended time to complete a degree, medical leave of absence.